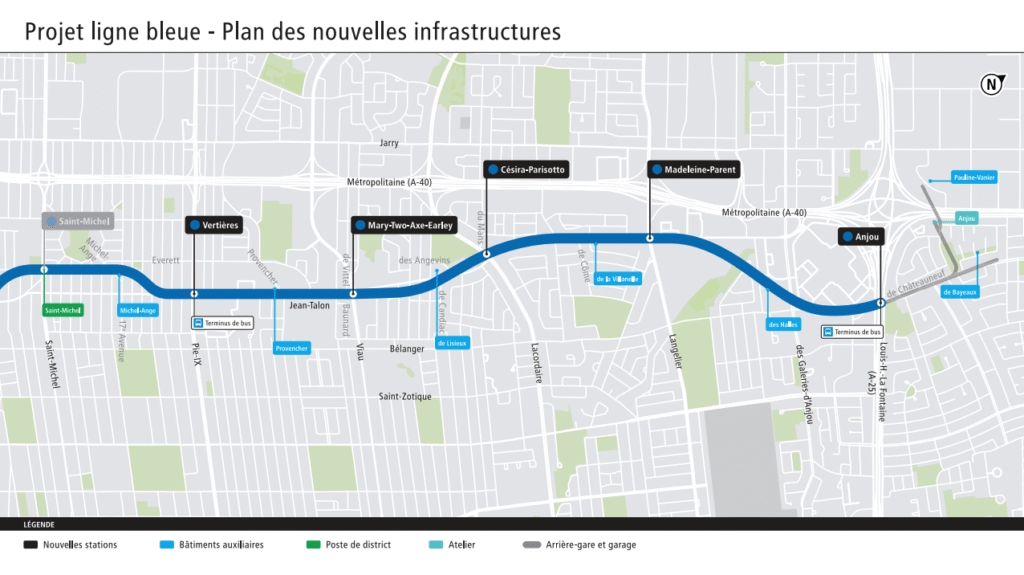

Roger-Luc Chayer (Image : Société de transport de Montréal)

It was almost unanimously that Montrealers expressed yesterday, during the unveiling of the new names for the Blue Line metro stations, their profound surprise and disagreement regarding the choices made as well as the way Mayor Valérie Plante proceeded. At the end of her term, since she will not even be running in the municipal election in November, the mayor is once again exposed to criticism.

During an interview yesterday evening on Radio-Canada with Patrice Roy, Valérie Plante stated that she wanted to give a greater place to women, who had been almost absent in the naming of Montreal metro stations. Traditionally, stations were named after neighborhoods or nearby streets, which anchors their identity in the urban reality.

Following the fiasco of Place des Montréalaises — a concrete space behind City Hall that cost 100 million dollars — comes now the issue of the new station names, assigned without any public consultation. Many see it as a whim of the outgoing mayor, a sort of personal legacy, while acknowledging that she had not succeeded, in eight years of office, in creating a consensus around her vision of the city.

During the interview, when Patrice Roy asked her whether she was aware of the numerous failures related to bike lanes, closed streets, orange cones, the pharaonic financial management of City Hall, or the fact that her designated successor, Luc Rabouin, is already distancing himself from her recent decisions, she simply replied that she was proud of what she had accomplished “for a part of the population,” meaning her most loyal voters. At times, her performance gave the impression of hearing Donald Trump deliver his “alternative facts,” regardless of reality.

Explanation and history of the new station names

Vertières Station

Vertières is the name of the site near Cap-Haïtien where the decisive battle on November 18, 1803, took place between the Haitian indigenous army and Napoleonic troops. This military victory ended more than a decade of struggle and paved the way for the proclamation of Haiti’s independence on January 1, 1804, the first free Black republic in the modern world. The name Vertières thus became a national symbol and a point of memory, embodying the courage of former slaves and their leaders who defeated one of the most powerful armies of their time.

In this regard, it is somewhat relevant to give the station the name of an important victory of the Republic of Haiti, as it will be located at the corner of Jean-Talon and Pie-IX and will mainly serve the population of Montréal-Nord, a borough largely represented by descendants of Haiti.

Mary-Two-Axe-Earley Station

This station is the most contested and controversial for several reasons. The first, and most obvious, is the lack of adherence to Montreal’s traditional francophone naming conventions. Indeed, it is a proper name, but what is the connection to Viau Street in Saint-Léonard? Let’s talk a bit about this woman…

Mary Two-Axe Earley was a Mohawk activist from Kahnawà:ke who played a central role in the fight for the rights of Indigenous women in Canada. Married to a non-Indigenous man, she was a victim of the discriminatory provisions of the Indian Act, which stripped Indigenous women of their status when marrying a non-Indigenous man, while men retained their rights. From this personal injustice arose a long political and social struggle that she pursued tirelessly from the 1960s onward.

An additional issue: Mary Two-Axe Earley belonged to an Indigenous people that does not recognize the sovereignty of Montreal. Paradoxical, isn’t it? The Mohawks of Kahnawà:ke consider Montreal as located on unceded territory, occupied without their consent. This does not mean there is no relationship: in practice, there are economic, social, and cultural collaborations between the Mohawk community and the metropolis, but they take place in a climate where Mohawk sovereignty is constantly asserted.

Césira-Parisotto Station

This metro station, which will be located at the corner of Jean-Talon and Boulevard Lacordaire in Saint-Léonard, is somewhat relevant to the population it will serve, even if the name of this nun is not easy to remember. Who was Sister Césira Parisotto?

Sister Césira Parisotto, born May 31, 1909, in Italy under the name Césira Parisotto, is a prominent figure in Quebec’s religious and philanthropic community. A member of the Sisters of Charity of Sainte-Marie, she took her vows in 1928 and dedicated her life to charitable works, notably in Italy, Ethiopia, and Canada. Arriving in Montreal in 1949, she founded several institutions, including Hôpital Marie Clarac, École Marie Clarac, Camp Mère Clarac, and residences for the elderly. Her commitment to the underprivileged, regardless of race, language, or religion, earned her distinctions such as the Order of Canada and the National Order of Quebec. She passed away on December 16, 1992.

The name of this station and the memory of this nun constitute a very relevant gesture, reflecting, for once, an excellent decision by the city of Montreal.

Madeleine-Parent Station

Located at the corner of Jean-Talon and Langelier, this station has no direct link to Langelier Street, the borough, or the history of the area. Its name was chosen arbitrarily, for honorary purposes, which is not necessarily a bad thing.

Madeleine Parent, born in Montreal in 1918, was a leading syndicalist and feminist activist in Quebec. From a young age, she engaged in defending workers, especially in industries where women were the majority, such as textiles. Her work focused on fighting for fair working conditions, pay equity, and recognition of women’s rights within the labor movement. She courageously faced opposition from employers and sometimes authorities, using her determination and intelligence to mobilize workers and build strong unions capable of defending their interests.

Madeleine Parent is among the strong women of Quebec, such as Marie-Joseph Angélique, Thérèse Casgrain, Viviane Gauthier, and Louise Arbour, who helped shape the modern nation we know today.

Anjou Station

Unlike the other names, this metro station is entirely relevant given its location, namely in Anjou, an important borough of Montreal. On this point, nothing to criticize.

The borough of Anjou takes its name from the French province of the same name, in honor of the European origins of several settlers who arrived there in the 19th century. Initially a rural and agricultural territory, it gradually became part of Montreal’s growth. The name Anjou thus evokes both the history of the first inhabitants and the continuity of a local identity within the Quebec metropolis.

And where are the famous LGBTQ+ personalities?

Set aside Laurent McCutcheon at the end: not only was he not an angel, this rascal, but there are many others who would have deserved the honor of giving their name to a first metro station.

Unfortunately, to this day, there is no metro station in Montreal named after an important person for the LGBTQ+ community. No explicit toponymic tribute has yet been dedicated to a key figure in this community. Could yesterday have been an opportunity to make a first announcement in this regard? Of course.

But Mayor Plante is not new to mistakes. Michel Tremblay, Édith Butler, Xavier Dolan, Monique Giroux, Jean-Paul Gaultier, and many others could have been honored, and it is not necessary to be deceased to receive this tribute.

ADVERTISING